As someone who studies history, I often think about how our understanding of the past is shaped by our capability to remember and also to preserve. In my past experience at the colonial archives, I was thrilled to look through handwritten correspondence, but I always felt that my historical interpretation was like guessing at the image of an infinite-numbered piece puzzle while only possessing a few of its pieces. With the rapidly increasing amount of digital culture produced through websites, blog posts, and social media, researchers can get a more and more multifaceted view of an individual’s life. However, how and what should we preserve for future generations and for research? What is deemed valuable (and financially feasible) for preservation? And does this archived information perpetuate a certain uneven representation of the past?

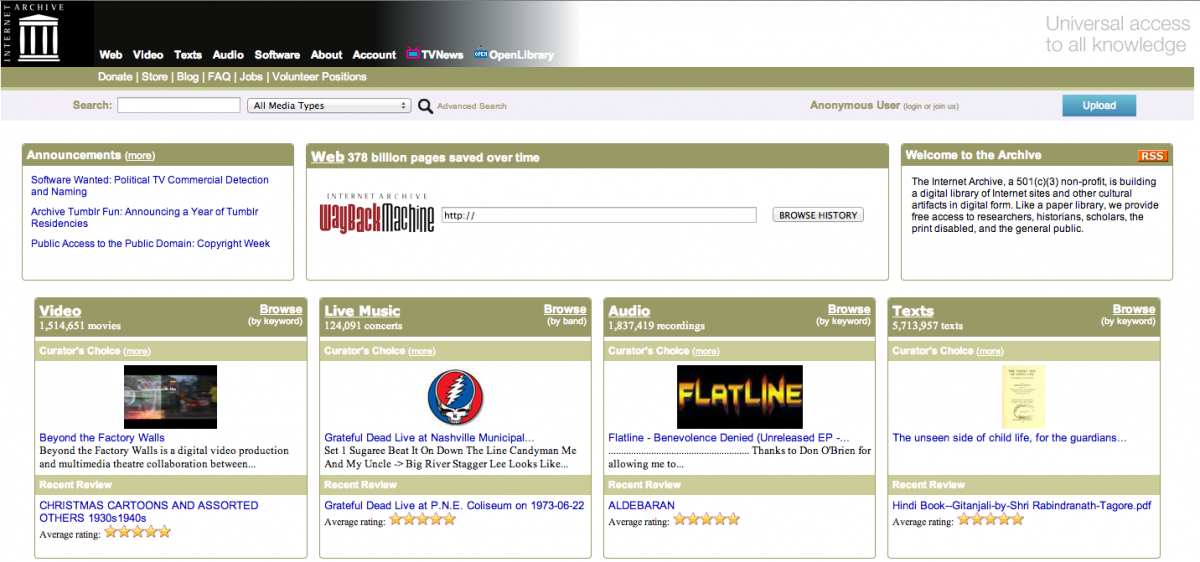

Besides the famous Twitter Archive at the Library of Congress, the Internet Archive has also been at the forefront of archiving websites and texts to video and software. However, the vast and increasing amount of digital information about people, places and events has posed a challenge for simple solutions and standards for how to archive it for future generations and researchers. The following blog post (originally published on the blog of the Townsend Center for Humanities) addresses some of the issues of digital preservation and archiving. Yet, I also wonder too how digital preservation differs or resembles traditional modes of preservation.

Furthermore, more and more digital humanities projects have contributed unique ways to chronicle the past and also display information in innovative and insightful ways. (For some examples see Slate’s Top Five Digital History Sites.) Yet, these projects themselves need to be preserved, especially given the constant changes in technologies, platforms, web hosting services, and funding sources. A recent article on digital preservation of digital humanities projects at University of Virginia has reiterated the cost of both building and maintaining a digital project. If we want our digital work to have meaning beyond the present, preservation deserves real hands-on attention and must be an important part of earlier development stages of a project.

------

"Digital Dark Age or TMI?" by Suzanne Scala (Originally published on the Townsend Center for the Humanities Blog on July 25, 2013)

On October 1, 2013 the Townsend Humanities Lab—a four-year exploration of digital tools for the humanities—was retired. Archiving the site provides an occasion to reflect on digital archiving in general. What happens to all those unpublished website files saved on hard drives? Or how about the boxes of floppy disks out there? Do we even care? Some say that TMI (Too Much Information) is the Internet culture’s catchphrase, but others argue that it's worth preserving everything from dissident websites disabled by repressive governments to all the celebrity tweets about the name of the royal baby.

Organizations like the Internet Archive (hosts of the fascinating Wayback Machine, an archive of 240 billion web pages going back to 1996) and the California Digital Library argue that our digital culture is important, and they’re working to make sure it is available for generations to come. If we manage to successfully archive our current digital culture, researchers of the future could have intricately detailed snapshots of historical moments. Historians studying the revolution in Egypt, for instance, would have access not just to relevant documents and news reports, but a view of the whole world's reaction—moment by moment—on social media, blogs and web sites.

Yet, especially in places like the EU, some of this archiving runs counter to laws and ethics of privacy. In France, lawmakers are championing what they call “the right to be forgotten,” which would allow people to delete information about themselves (like drunken party photos) that they’d rather keep private. When they heard about this, French archivists took to the streets to try to preserve important historical information for the future. And they aren't alone. The NSA, other governmental bodies, and web companies like Google are also quite interested in preserving our ephemera. With such powerful interests in favor of information archiving, perhaps we’ll find the problem isn’t preserving our information after all, but gaining public access to it.

Despite all the corporate and state interest in collecting information, supercomputer designer Danny Hillis argues that we are nonetheless entering a “digital dark age” in which our archiving technologies won’t outlast us. How will future historians know anything about our society if we keep all of our information on media destined to become outdated and unusable? While we can keep transferring our data to more modern media as technology evolves (VHS—> DVD—> mp4—> ??), we won’t necessarily make the choice to preserve what future researchers will find useful. Scientists in the Netherlands, for instance, have used data from the CIA's recently declassified CORONA satellite spying program to track climate change. Yet according to the National Reconnaissance Office's Fact Sheet, this data is comprised of "2.1 million feet of film in 39,000 cans" that is subject to degradation and obsolescence over time.

Today, we’re knee-deep in information about our digital culture. To see for yourself, visit Harvard’s Tweet Map; a recent comparison of “royal baby” and “economy” was depressingenlightening. Since we don't know what will be important to future researchers, it seems sensible to archive as much information as we can. Yet, given the amount of data we create, such a task might be too big and expensive a job.

-----

For more on the topic of digital archiving, watch a video of Diana's Taylor's 2010 lecture, "SAVE AS... Memory and the Archive in the Age of Digital Technologies."

For more humanities blogging from the Townsend Center go to http://townsendcenter.berkeley.edu/blog